Introduction

As you dive deep into the world of Mughals, you will see a vibrant Indo-Persian visual culture depicted through Mughal architecture and paintings. In terms of architecture, aesthetics, glamour, and size are more likely to awe people with the power and prestige of the empire. But paintings were expensive and time-consuming, and only a few nobles had access to them. Moreover, the orthodox Islamic tradition has put restrictions on painting the likeness of humans. Despite these religious restrictions, Mughal court painters did not shy away from rendering human figures, especially that of spiritual significance.

Background of Mughal Visual Culture

To understand why Mughals were so keen on paintings, let’s look at the cultural milieu of the 15th and 16th centuries. Babur mentioned Behzad, the most famous painter of Kabul, in his memoir. For him, art appreciation was not just about evaluating paintings of artists of his times but also about gazing at the world through the lens of art. He wrote in his memoir about the beautiful foliage of an apple sapling and remarked, ‘no matter how much efforts painters would exert they never can depict such a thing’. Therefore, we can say that the Persianising elite of India and Iran were gradually seeing themselves and their surroundings through the painted images.

The court paintings mostly depicted kings and prophets. Courtly merriment, victories in battles, and the Prophet’s journey to heaven were favourite themes for the painters. But how could these paintings flourish with long-held Islamic restrictions against images of human beings? During this period a new Islamic art historical narrative emerged. This narrative revered the practice of painting among ancient Biblical prophets.

Chest of Witnessing tradition is a story about the Companions of the Prophet who visited the emperor of Byzantium. The emperor showed them a chest with thousands of compartments, each containing an image of a prophet. The Persian word for ‘Chest’ also means a container of revealed truth. Since this tradition is mentioned in all millennial histories of Akbar, image-making began to be seen as a divine practice, rather than a form of idolatry. Another source for the image-positive narrative is the Hurufi strand of Islamic mystical tradition which associates painting with the sacred art of calligraphy.

Also Read: The history behind Mughal Miniature Paintings

Competing Legacies of Mughal Emperors

No Mughal emperor could even imagine outdoing Akbar in terms of his conquest. The same goes for the production of aesthetic monuments and paintings that celebrated his sovereignty. Hamazanama (Book of Hamza), produced under Akbar’s reign, had 1400 poster-size paintings and took ten years to complete.

Akbar also ordered translation and illustration of Hindu epics, Ramayana and Mahabharata. His monstrous biography written by Abul Fazl had hundreds of illustrations of his reign. In the last years of his life, his son Salim, who later named himself Jahangir, challenged his authority. He questioned his father’s decisions and tried to gather support from the section of nobility that was not content with Akbar’s policies.

Once he became the Emperor, Jahangir decided to keep a diary which his dyslexic father could not do. Since he could not compete with his father in the amount of paintings made, he adopted a different style and content. Instead of commissioning grand illustrated epics or histories, he ordered highly innovative paintings and ultimately broke the preceding tradition of Persian miniatures.

Imperial Themes in Paintings of Jahangir’s era

The paintings Jahangir commissioned were not just about aesthetics or representation. They presented a highly sacred image of Jahangir through unique and intricate symbolism. While his memoir narrated his worldly doing, paintings depicted his mystical character. By projecting himself as a saintly being he claimed to have thaumaturgic ability to impose his will on the world.

Ajmer had held a great spiritual significance for the Mughals. It was believed that Jahangir was born by the blessings of a Chishti saint. Muinuddin Chishti was considered the saint of the Mughal dynasty. The Mughal rulers often visited his shrine. In his memoir, Jahangir called himself a slave and disciple of the saint, but interestingly, he made no such submission in the paintings.

Also Read: The origin and evolution of Miniature Paintings in India

Jahangir’s interaction with Chishti Saint

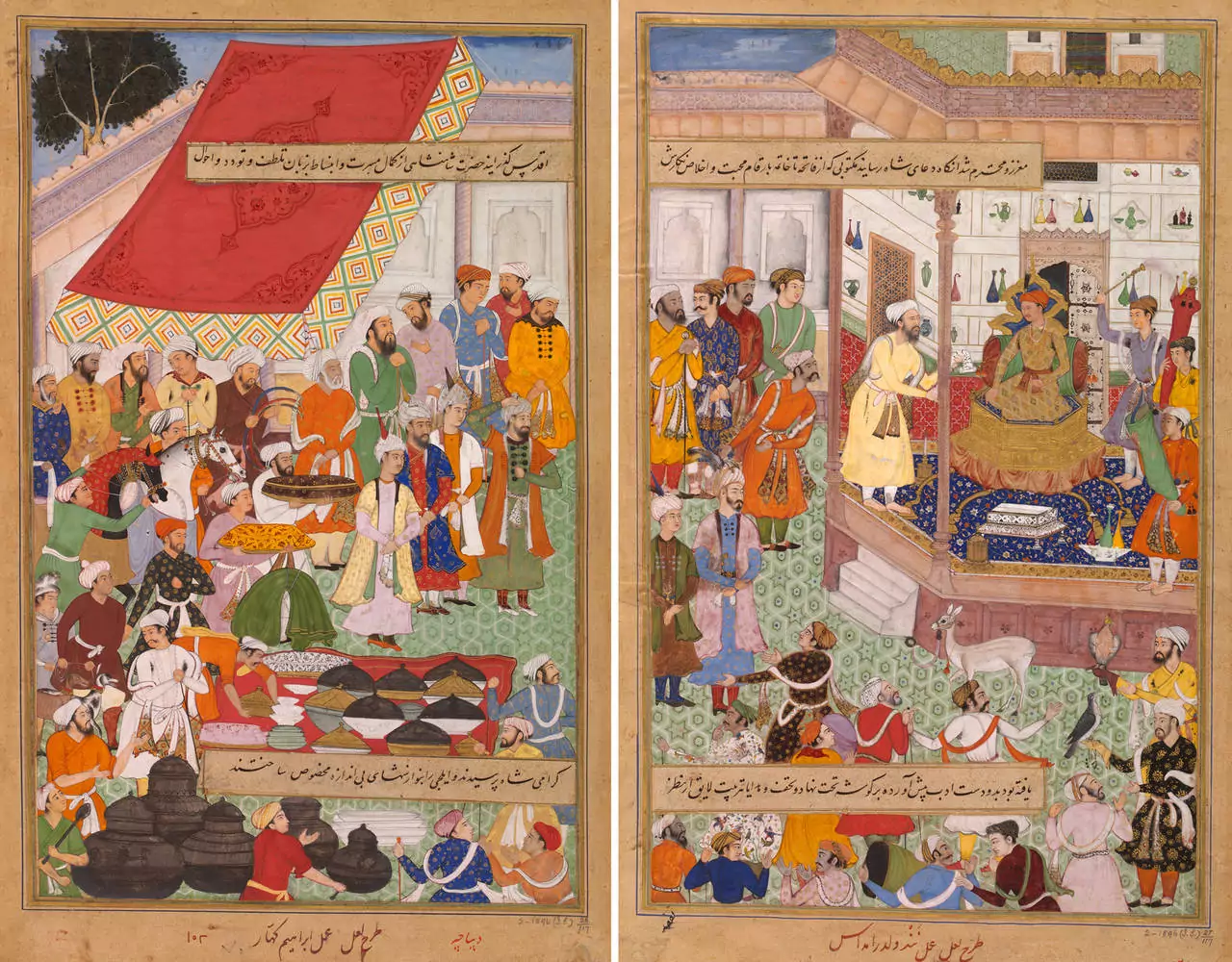

These two paintings are drawn on the facing pages of an album. On the left, the whole page is devoted to the Sufi saint who is holding a globe with a keyhole and a crown. The key is faced upwards, away from the keyhole. He is holding the objects in his hands as if he is offering them to someone else. The Persian script written on the globe says, “The key to the conquest/opening of the two worlds is entrusted to your hands.”

On the right-facing page is the painting of Jahangir. He is a sole figure like that of Sufi. In his case, the key is pointed toward the keyhole rather than away from it. He receives the globe from the Sufi in his right hand while his left-hand rests on the sword. The globe has different lines now. They say mastery over the two worlds, material and spiritual, lies with Jahangir. The paintings present an act of succession from Muinuddin Chishti to Jahangir, one saintly being to another.

These two paintings are different from others that show the Mughal Emperor’s interaction with Sufis. Here, Jahangir meets the holy man who has lived five hundred years from him on a metaphysical plane. On this metaphysical plane, light emanating from their halos pierces through the surrounding darkness. From such an elaborate interpretation, we can draw that these paintings marked the emergence of new visual culture.

Jahangir as a Divine Magician

In this miniature, Jahangir is shooting an arrow at the severed head of a dark-skinned man. The severed head on the lance belongs to Malik Amber, a military commander of Abyssinian slave origins who became the real power behind the throne of the Nizam Shahi dynasty of Ahmednagar. As an enemy of the Mughals, he prevented Jahangir from spreading his control in Deccan.

Though Jahangir could never capture Malik Ambar, this painting still holds a small element of historic reality. It portrays an incident mentioned in Jahangirnama, which happened right before Prince Khurram (the future Shah Jahan) set out to march into Deccan to capture Malik Ambar. An owl had perched on the palace roof. Since owls symbolised violent death, Jahangir took it upon himself to shoot down the ill-omened owl.

Jahangir, pointing his rifle at the living owl perched on Ambar’s head, is set on the metaphysical plane. The Mughal Emperor occupies the axis of the earth, the position reserved for the saint of the age. By asserting himself as the centre of the cosmos, he acts as a cosmic agent who strikes a balance between good and evil and kills the demonic force that the owl and Ambar symbolise.

It was not the first time a Mughal Emperor attempted to curse and kill an enemy through a talismanic painting. Young Akbar had drawn a dismembered Hemu to miraculously destroy his enemy and refused to kill him on the battlefield as he already killed him once in his sketch.

Jahangir as the Restorer of Justice

Jahangir again is standing over the axis mundi and shooting an arrow at a naked, emaciated, dark-skinned old man. The description says that ‘Majesty’s arrow of kindness destroys dalidar from this world and recreates the world anew with his justice and fairness’. Dalidar is the Hindi word for poverty. In the Diwali festival, people get rid of the goddess of poverty, Daridra, and clean their homes to welcome Lakshmi. Therefore, Jahangir is performing a renewal ritual to create a new world of prosperity and justice.

Through this painting, Jahangir claims to have an association with Hindu Kingship. Rama is a god-king who has inaugurated a new cycle of time by destroying demons, corruption, and disorder. Akbar had declared himself as the reincarnation of Rama and following his steps, Jahangir also did the same. Mughal Emperors actively participated in the public culture and celebration of festivals to extend his sovereignty to every section of society.

Jahangir’s Imagination: The Visual Record of Imperial Dreams

According to the commentary on the painting, Shah Abbas, Sultan of Iran, visited Jahangir in his dream. The emperor immediately told his painters to paint his dream, telling us how innovations in paintings bear the stamp of his imagination. In the painting, Shah Abbas hugs him as a sign of friendship, but the hierarchy is well maintained. While Jahangir projects himself on a lion, Abbas is atop a sheep. Through this symbolism, Jahangir claims to represent a world of peace and harmony where the weak can live side by side with the strong. One interpretation hints at Jahangir’s anxiety over losing Kandahar to the Safavids. Another interpretation points to how the Mughals saw dreams as a medium of miracles and prophecies. Jahangirnama tells us how dreams he dreamt have justified his actions and policies. Therefore, dreams fed into the social discourse of the time as they translated into real-life events.

This painting also depicts Jahangir’s dream. He appears to be in the company of people he had never met in real life. Rather than standing on a globe, he stands on an hourglass. The two greatest monarchs of the world, the Ottoman sultan and King James I of England, and a mystic compete for Jahangir’s attention. Jahangir sitting on the throne of time inaugurated the new Islamic Millennium which brought an end to the struggle over bringing the world back to order by making the hierarchy clear. The Sufi gets more proximity to Jahangir than other kings signaling that Sufi is above the Kings and Jahangir is above all of them. Putti are nude chubby child figures that appear in mythological and religious artworks of Renaissance. In the painting, the Mughal Emperor no longer needs arrows from Putti as the world has become peaceful.

Also Read: Traditional art forms and its role in storytelling

The Tradition of Sacred Kingship among Mughals

Once Jahangir became the emperor he realised the importance of Akbar’s legacy. He continued with the tradition of Sacred Kingship that Akbar established. He welcomed all religions in his court without feeling the need to adopt one. The sacredness he identified himself with situated him above all religions. Both Akbar and Jahangir demanded discipleship from their subordinates to prove their loyalty. If closely studied, court paintings can give us a great insight into the minds of the Emperors and what ideas typical of that period had influenced them. We can learn about subjectivity and how the elite saw the world around them.

Download the Rooftop App from GooglePlay or AppStore and enroll in our maestro courses!

Discover us on Instagram @rooftop_app for all things on traditional Indian art.